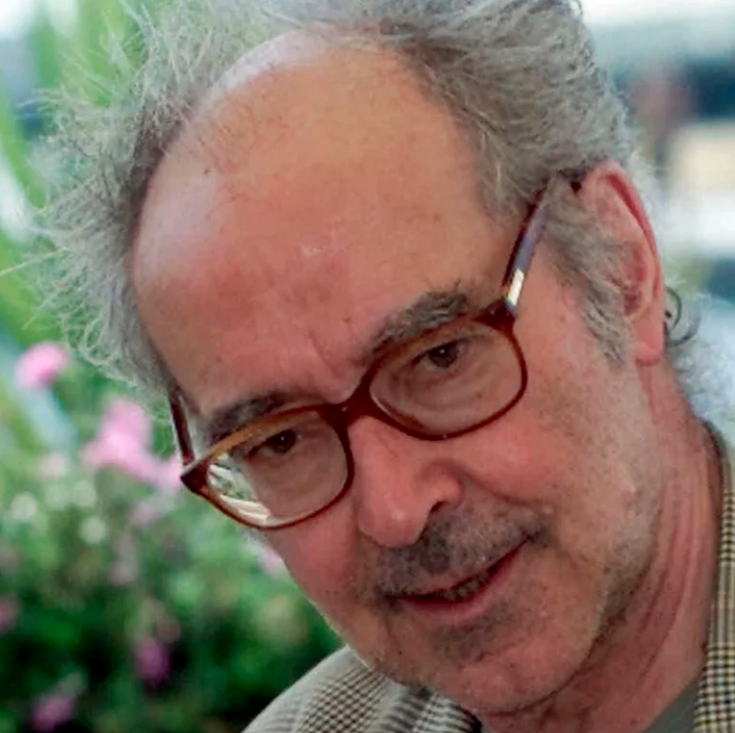

Jean-Luc Godard, 91, was a French film director. He was a key figure in the New Wave film movement. Let’s take a closer look at how he died and Jean-Luc Godard’s cause of death.

Table of Contents

How did Jean-Luc Godard pass away?

“Breathless”. Jean-Luc Godard died at the age of 91, according to information released by our colleagues at Liberation on Tuesday, September 13.

The Franco-Swiss filmmaker was best known for his films “Le Contempt,” “Breathless,” and “Pierrot le Fou.”

Jean-Luc Godard began his career as a film critic in the 1950s while making short films before making his first feature film, “A bout de souffle,” in 1959, while inhabiting the skin of the main character, actor Jean-Paul Belmondo.

Cause of death for Jean-Luc Godard

A French cinema legend has died of natural causes. Jean-Luc Godard died on Tuesday, September 13, at the age of 91, according to his family. Despite this, no official information on Jean-Luc Godard’s cause of death has been released. The Franco-Swiss filmmaker leaves a legacy of masterpieces that have influenced many generations.

Jean-Luc Godard, like his contemporaries Claude Chabrol and François Truffaut, began his career as a film critic before becoming a renowned director. However, once behind the camera, the filmmaker transformed the world of the Seventh Art.

Medico topics have attempted to contact the victim’s family and relatives for comment on the incident. There have been no responses so far. We will update this page once we have enough information on Jean-Luc Godard’s exact cause of death. More details about Jean-Luc Godard’s Cause of Death will be added soon.

Who is Jean-Luc Godard?

Jean-Luc Godard is a French-Swiss film director, screenwriter, and film editor who has worked for more than sixty years. Many of his films have been directed, written, produced, and edited by him. The following is an attempt at a comprehensive filmography.

Early life and career

Godard spent his formative years working in his father’s clinic on the Swiss side of Lake Geneva. His academic training included coursework for an ethnology degree at the University of Paris, endless discussions in student cafes, and laboring on a dam, which served as the inspiration for his debut short film, Opération Béton (1954; Operation Concrete).

His interest in ethnology is related to the influence of anthropological Jean Rouch on his work as the first practitioner. And theorist of the documentary-style film style cinéma vérité (also spelled “cinema truth”).

The film’s concept and motifs emerge only during filming or later, during the editing process, thanks to the filmmakers of this school’s use of basic television equipment to view their subject with maximum informality and total objectivity.

Jean-Luc Godard’s awards and later work

Sauve qui peut (la vie) (Every Man for Himself), a story about three young Swiss individuals and their struggles with work and love, marked Godard’s return to successful narrative feature filmmaking in 1979. In the 1980s, he worked on film projects in his home country, California, and Mozambique.

His “trilogy of the sublime,” which included three films—Passion (1982), Prénom Carmen (1983; First Name: Carmen), and the contentious Je vous salue, Marie (1985; Hail Mary)—that served as personal statements on femininity, nature, and Christianity, is widely regarded as his most significant work of the decade.

Television documentary in multiple parts

Rather than directing many feature films in the 1990s, Godard focused on the multi-part television documentary Histoire(s) du cinéma, which presented his controversial views on the first 100 years of motion picture history. Éloge de l’amour (2001; In Praise of Love), a narrative film that examined the nature of love and life in movies, sparked controversy with its harsh criticism of Hollywood filmmaking.

Adieu au langue (2014; Goodbye to Language), a fragmented story about a man, a woman, and a dog, was shot in three dimensions. Notre musique (2004; “Our Music”), a meditation on war; and the experimental collage Adieu à la langue (2010; Film Socialism); and Film Socialism (2014; Goodbye to Language). Le Livre d’image (2018; The Image Book) is a cinematic essay that combines a montage of World War II film stills, images, and videos. Throughout the piece, Godard provides commentary. Godard received numerous honors, including honorary Césars (1987 and 1998), the Japan Art Association’s Premium Imperiale for theatre/film (2002), and an honorary Academy Award (2010).

Jean-Luc Godard: a filmmaker seeking renewal

After the success of his film Alphaville at the Berlin Film Festival in 1965, Jean-Luc Godard decided to shift his focus to more committed and political feature films.

Cinema, he believes, is a means of combating the system. After Jean-Luc Godard was killed in a motorcycle accident in 1971, a turning point inspired by the nervousness of May 1968 slowed in mid-flight.

If he was absent from the set for an extended period of time, the director quickly returned to his first love. He made a big comeback behind the camera in the 1980s.

Jean-Luc Godard becomes one of the most coveted filmmakers by introducing “cinematographic modernity.”

Great actors, such as Nathalie Baye and Jacques Dutronc in Sauve qui peut la vie or Gérard Depardieu in Hélas pour moi, have frequently fought their way into front of the camera.

Godard made several experimental films in the decade that followed, including Histoire(s) du cinéma. Since the 2000s, the producer has been much more subdued on stage. His work, however, has continued to impress and be recognized.

After winning the Jury Prize at Cannes in 2014 for the film Farewell to Language, he was awarded the special Palme d’Or for The Image Book in 2018.

Jean-Luc Godard has established himself as one of the most original filmmakers concerned with breaking cinematic codes throughout his career.

The director has written a chapter in the history of the Seventh Art over the last half-century. If Jean-Luc Godard leaves many moviegoers orphaned, he also leaves behind his last wife, actress and director Anne-Marie Miéville.

Influence on modern film

“He comes along in 1960,” critic David Thompson told NPR’s David D’Arcy, “and says in effect, I have seen all the films ever made. I love them, most of them, but I abandon them because they’re all out of date. I am going to make a new kind of film, and I’m going to combine the energy and the novelty of ideas of a student, with the story forms of the old films. And for six or seven years, two films a year so we’re talking about a fair number of movies, he pulls it off.”

In pictures like Contempt, with Brigitte Bardot and Jack Palance, in which he indicts commercial filmmaking; in his science fiction film Alphaville, which places a private eye in a society run by a computer; and most memorably in his scathing, satirical takedown of middle-class materialism, Weekend, a black comedy involving murder, cannibalism and an eight-minute, single-shot traffic-jam-on-a-country-road, that is among the most celebrated film moments of the 1960s.

Weekend premiered just weeks before student and worker protests shut down much of France in May of 1968. Godard, leading a protest that closed the Cannes Film Festival that month, told the crowd that not one of the films in competition represented their causes.

“We are behind the times,” said this leader of the French New Wave. And in that moment, his filmmaking took a turn. He embarked on a decade of deliberately revolutionary movies — low-budget provocations, non-commercial, shot in Palestine, Italy, Czechoslovakia, and filled with a Marxist fervor. Tout Va Bien, for instance, starring Yves Montand and Jane Fonda in the story of striking workers at a sausage factory.

Godard’s evolution as a creator

This overt emphasis on politics was itself a phase, and by the 1980s, Godard was looking inward and looking at film itself. As his art matured he grew less interested in narrative and more in experimenting, though he’d actually, always been experimenting.

In a public debate in 1966, he kept calling film grammar itself into question, until an exasperated panelist finally sputtered, “Surely you agree that films should have a beginning, a middle part, and an end.”

“Yes,” conceded Godard, “but not necessarily in that order.”

Godard had come to film in his early 20, he told NPR.

“My parents told me about literature, some other people told me about paintings about music, but no one told me about pictures.”

So he told others. He began as a critic and, in a sense, he remained one all his life in famously quotable public statements: “All you need to make a movie,” he once said “is a girl and a gun.”

But as time went on, he was happy to dispense with both girls and guns, and also with plots. A difficult man by nearly all accounts, he feuded with his contemporaries (an argument with his friend and fellow New Wave director Francois Truffaut over the latter’s Day for Night in 1973 wasn’t resolved before Truffaut’s death in 1984). And in his later years, he dismissed notions that contemporary Hollywood could ever make serious films.

If Godard’s own work was serious by his lights, in his final decades, it mostly consisted of what might be called visual “essays” — collages of film-and-video clips accompanied by sound and sometimes impenetrable commentary — that found smaller and smaller audiences.

But what he achieved in the early 1960s is still with us, his innovations so absorbed by the mainstream that he has continued to influence filmmakers, some of whom may barely have heard of him, long after the New Wave got old.